THE “AGE OF THE WEATHER KIOSK”

Coburg, Germany

Llmenau, Germany

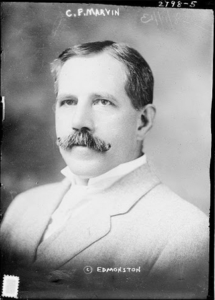

Charles F. Marvin, Professor in charge of the Instrument Division of the US Weather Bureau

EUROPEAN ORIGINS

The concept to have a centrally located structure from which to obtain current weather information dates back to the mid to early 1800’s in Europe, they are not called “weather kiosks” but Wettersäule or “Weather Column.”

This was likely because the original designs were tall, narrow structures that helped record more accurate wind measurements and were more visible.

The first Weather Column was built in 1838 in Geneva, Switzerland, on the Grand Quai. These weather columns gained popularity across Europe during the 19th century. By the end of the century at least 600 were built across Europe, and were especially popular in Switzerland and Germany.

While the U.S. weather kiosk designs were standardized across the country, the weather columns in Europe were built in a wide array of shapes, sizes, and heights. This was due to the fact that they were built by many different individual cities, organizations, and individuals each with their own design and implementation.

U.S. TESTS & BEGINS INSTALLING KIOSKS

Eventually, the idea to build weather kiosks caught on in the U.S. and the Weather Bureau decided to implement the idea across the country. Since many people still at this time received their weather information from the Farmers Almanac, the kiosk was viewed as a way to increase the visibility of the U.S. Weather Bureau. The Weather Bureau also described the need for “A suitable means of taking meteorological observations, especially of temperature and humidity, near the street levels, and thus representing more nearly the conditions experienced by pedestrians and the public generally.”

The U.S. Weather Kiosk was the invention of Professor Charles F. Marvin, who was in charge of the Instrument Division of the U.S. Weather Bureau. Professor Marvin was tasked with designing the kiosk and determining how to display the weather instruments so that the “every-day man” could read and understand its output. The kiosks included special forms of maximum and minimum thermometers, an air thermometer, a hair hygrometer, a thermograph, and a special type of rain-gauge with dial indicators. In 1908 the first Weather Bureau kiosk was built and installed in Washington D.C. It was considered a success and proved to be very popular among the citizens as not only a place to view the weather but as a meeting destination. After the successful test, the U.S. Weather Bureau began to build and install the kiosks across the country in 1909.

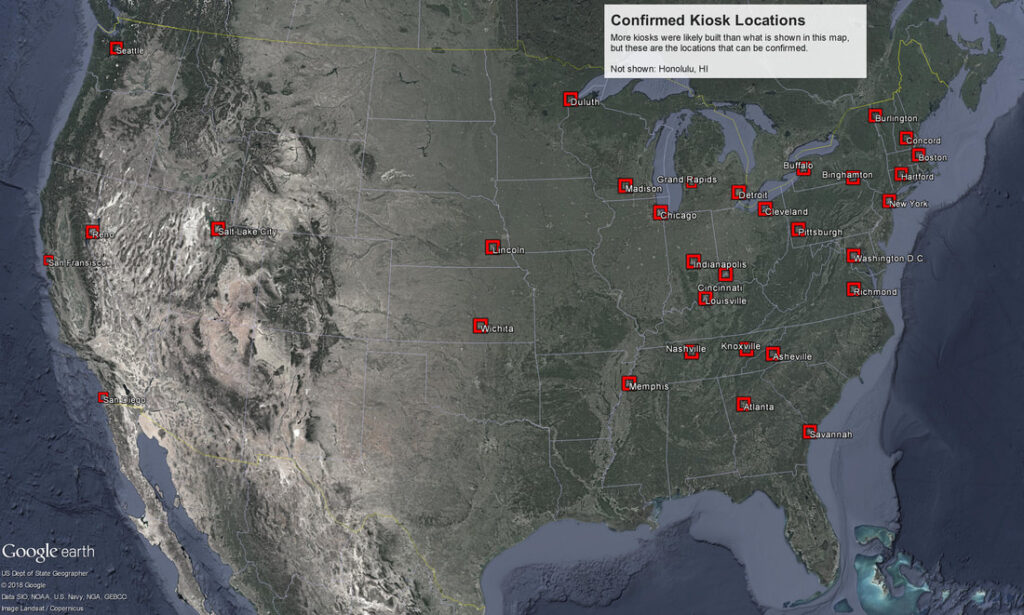

WHERE WERE THEY INSTALLED?

The accompanying map shows cities that are confirmed to have had a kiosk. Almost all of this information comes from local newspaper reports.(CLICK HERE TO ENLARGE)

Determining where these kiosks were installed presents challenges because the U.S. Weather Bureau documentation is very sparse on this topic. For example, in the 1909 report from the U.S. Weather Bureau states: “During the past year structures of this character, with their appropriate equipment, have been assigned to twenty-one of the more important cities of the country…”.

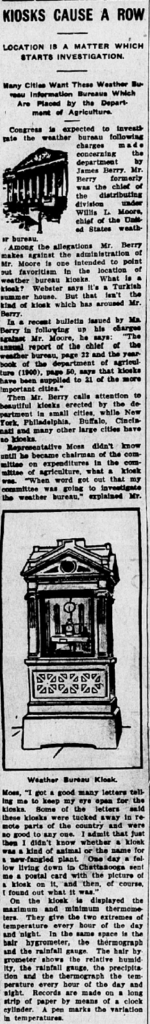

Article with accusations of favoritism for kiosk locations, Twice-a-Week Plain Dealer, Iowa, July 25, 1911.

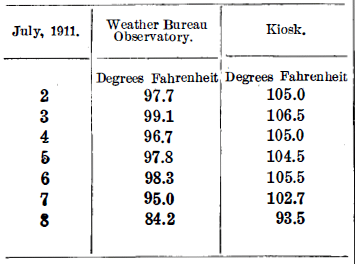

Readings from Washington D.C., July, 1911. Published in Scientific American.

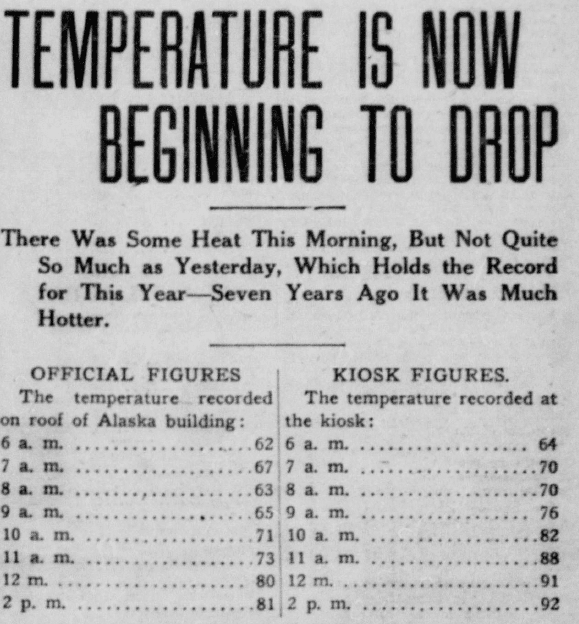

Article from Seattle Star, July 11, 1911.

MAJOR ISSUES & CONTROVERSIES

Though the age of the weather kiosk was very brief, during this short time there were several kiosk-related controversies, that in part, helped to bring about their discontinuation.

Location Controversy

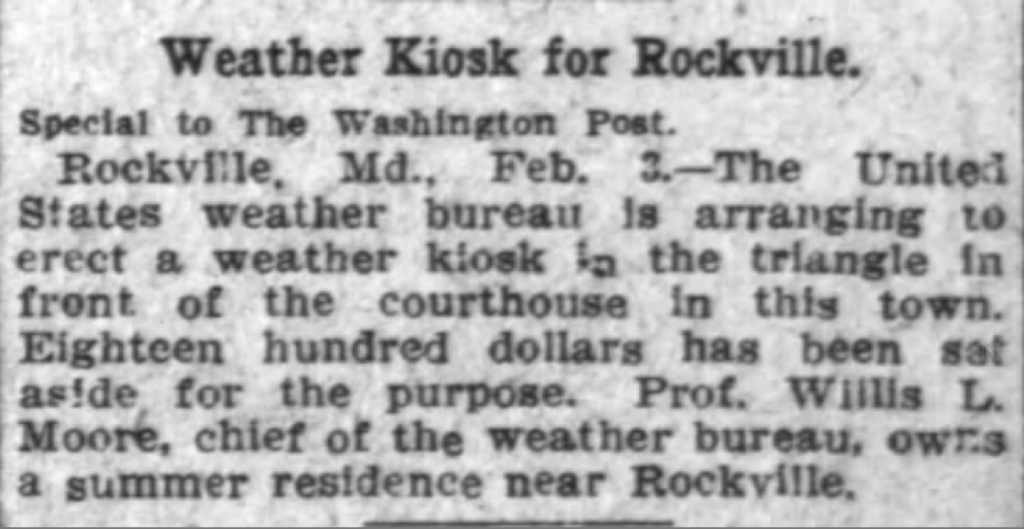

In the early 1910’s many cities wanted a weather kiosk, it was up to the U.S. Weather Bureau, however, as to which cities received them. Only approximately one dozen were constructed and installed in a year. Some citizens asserted political favoritism their placement. They began writing their congressmen to investigate these suspicions. One example is outlined in this newspaper clipping from the Washington Post, which indicates that one of the first kiosks built in 1909 was slated to be installed in Rockville, Maryland, where the highest-ranking employee of the U.S. Weather Bureau (Professor Willis L. Moore) had a summer home.

Incorrect Temperatures

One major concern was that the recorded kiosk temperatures often registered several degrees higher than the official temperature taken by the Weather Bureau. The official temperatures were usually taken on top of a multi-story building or in an open field near the city. Those temperatures at the kiosks were usually much warmer than those of the official record due to what is called the “Urban Heat Island Effect”. The “Urban Heat Island Effect” takes place when temperatures within a city, especially downtown locations, tend to be much warmer than the surrounding areas. Due to the materials used in cities (mainly concrete and asphalt) absorbing more solar radiation than the surrounding rural areas. All the kiosks were installed in central downtown areas so they could be seen by the greatest number of people, but it also meant that they were surrounded by hot buildings, sidewalks, and roads. The two examples, to the side, show the difference in temperature between the downtown Weather Kiosk and the official Weather Bureau temperatures, with kiosk temperature sometimes registering over 10 degrees warmer. This disparity was common across the country and a source of frustration for Weather Bureau forecasters and some city governments.

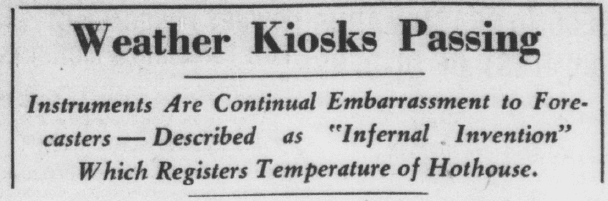

Forecasters and City Governments Displeased

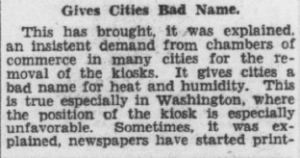

Over time, some of the biggest opponents of the kiosks were the forecasters at the U.S. Weather Bureau in cities where they were installed. Since the kiosks typically registered much warmer temperatures than the official readings the forecasters were constantly having to explain this discrepancy. Citizens questioned their official readings, and if people happened to look at the previous day’s forecast and compared it to what the kiosk registered, they would understandably assume the forecaster was wildly inaccurate. Some cities’ Chambers of Commerce also asked for the removal of the kiosks. During heatwaves, the exaggerated warm temperatures were printed in newspapers across the country, and some Chambers of Commerce assumed that people reading these headlines would think their city was simply too hot to be their next vacation destination.

Construction Stops, Existing Kiosks are Auctioned Off

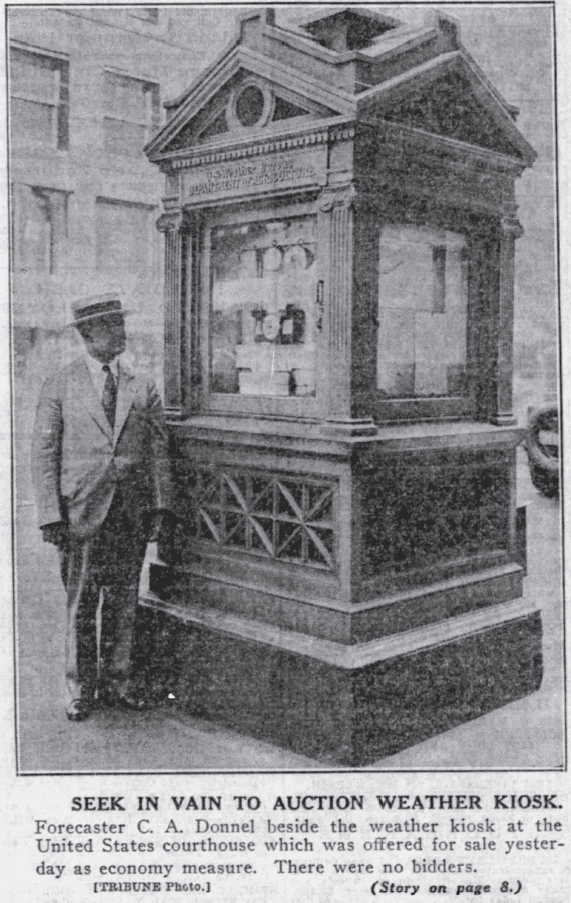

In 1914 the decision was made to stop the manufacture and installation of the kiosks, only five years after the original one was built and installed. Temporarily, the approximately 35 to 50 kiosks already installed across the country were allowed to remain. Over the proceeding two decades the kiosks in some cities continued to be a popular meeting destination and source of information while those in other cities were abandoned altogether. By the early 1930’s, only about half of the original weather kiosks were still in use. The Weather Bureau eventually decided that the approximately $25 per year to maintain the kiosks was no longer worth the investment, especially considering the rapid rise in popularity of the radio as a means of obtaining weather information. In 1933, the U.S. Weather Bureau sent a notice to the stations in charge of the remaining kiosks, informing them that they were to be discontinued and auctioned off to the highest bidder. Auctions were held across the country with the winning bids typically less than $5, and some of the kiosks went unsold. They did have valuable scrap metal in them that could be sold, but the major hurdle in selling the kiosks was the stipulation that the buyer must move it and repair the ground where it had been located. With the kiosks weighing in at 1.5 tons, this was a difficult and expensive feat that could cost in excess of $20.

Chicago Kiosk goes unsold, Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1933.